In 1987, the University of Mississippi held a symposium entitled “Covering the South: A National Symposium on the Media and the Civil Rights Movement” wherein participants discussed the influence of media on the civil rights movement. During one panel, a group consisting of eleven Pulitzer Prize winners and three Emmy awardees make huge claims about television’s role in the movement. CBS reporter Robert Schakne claimed that “Little Rock was the first case where people really got their impression of an event from television. It was the event that nationalized a news story that would have remained a local story if it had just been a print story.”[1] NBC news correspondent John Chancellor touted that reporters “were able to show [southerners] themselves on television. They’d never seen themselves. They didn’t know their necks were red. They didn’t know they were overweight. The blacks didn’t know what they looked like… [These images provoked] a profound reaction in both the black and white communities, because they’d never seen that, because we never see ourselves.”[2] While these comments are clearly disturbing in their simplification of southern self-awareness, they also illustrate a problematic and commonly held view of television’s relationship with historical events. For these journalists, it seems, television made these historical events important.

This, of course, is not a new sentiment. When Martin Luther King Jr. told the 1965 protestors in Selma, Alabama, “We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television,”[3] King himself acknowledged television’s capacity to influence political change. It is true that the television camera inspired hope in civil rights protesters who had been struggling for centuries to win freedom from white oppression with little reaction; they hoped television would make this protest different. Meanwhile, television news reporters, producers, and station managers sought to refute the popular perception of television as a novelty by covering legitimate stories to show their relevance. This relationship between political activists and reporters, in which activists promised to bring “news ready” drama and television reporters garnered journalistic validation by broadcasting the events, has given rise to the distorted that television’s importance is the national narrative it broadcasts.

This conception has inspired historians to argue that television brought issues like southern racism to the nation’s attention. We see this when in 1986 William O’Neill argues that television coverage of the protests “shamed and embarrassed Americans and was immensely helpful to the cause of civil rights” by mirroring “ugly white racists” against “neat, anxious, resolute black students.” [4] We also see this when Michael J. Klarman in 2004 argues that 1960s television actively dismissed “distinctive[ly] regional mores, such as Jim Crow” by promoting national values through uniform programming, [5] and that the racial violence “communicated through television to national audiences, transformed racial opinion in the North, leading to the enactment of landmark civil rights legislation.” [6] Even as recent as 2008, when Mackenzie and Weisbrot argue that other media formats, like newspaper and radio, allowed Americans to remain “complacent about [the] mistreatment of blacks,” while television forced American audiences to come to grips with the ugly images of racism. [7] Again and again, television is taking what was normally regional issues and making them national, which in turn makes television solely a national media entity.

The effect of this has been historian’s lack of focus given to how local television stations have operated. So powerful is the national narrative that many historians have questioned whether television even had an effect within their local community, and this skepticism is fundamentally flawed, as recent research by Classen and Mills shows. Local television stations had extensive control over what their viewers saw, with some stations going so far as to even censoring national broadcasts that were seen as not within their community’s interests.[8] They were also responsible for a substantial portion of the station’s programming. As one example, WSB-TV out of Atlanta, Georgia produced most of the four hours and forty five minutes of WSB-TV’s first day content locally and live on air, and the station was on air all seven days of the week. By 1951, WSB generated three to five hours of local content during a normal twelve hour day. In addition, while WSB operated as an NBC affiliate, it often aired content from the other three television networks, DuMont, ABC, and CBS.[9]

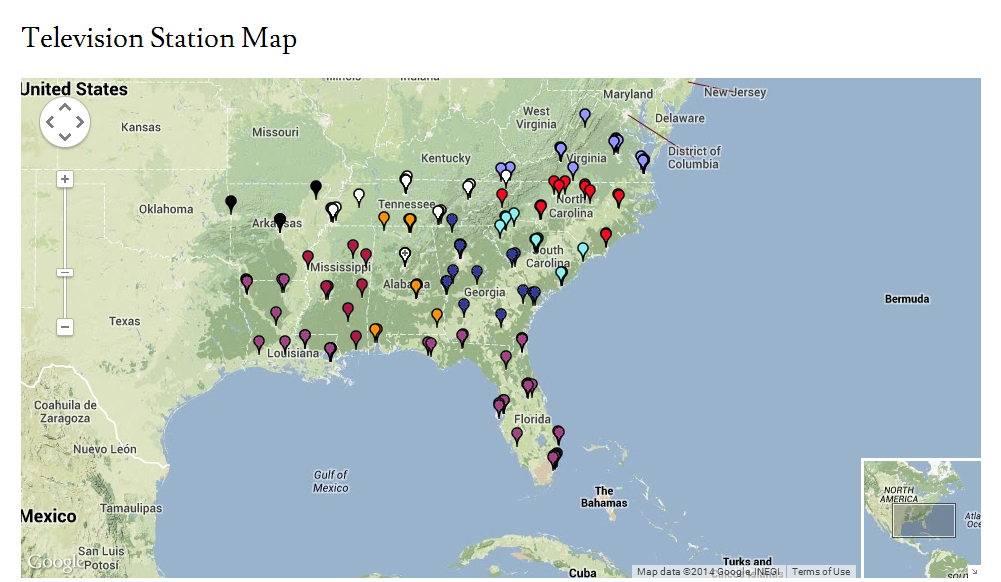

This is what inspires my research, and today brings us the launch of Visualizing Southern Television (VST) version 1.0. [http://vst.matrix.msu.edu] My drive with this project is to provide a visual interface that displays historical television coverage by local television stations, rather than focusing as most historians have up until now on the three national networks. The first part of VST is a fully functional map that documents every southern television station between 1942 and 1965. This map openly challenges previous assumptions that television stations were more important to non-southern states, by showing just how pervasive television was in the south. (See Figure 1)

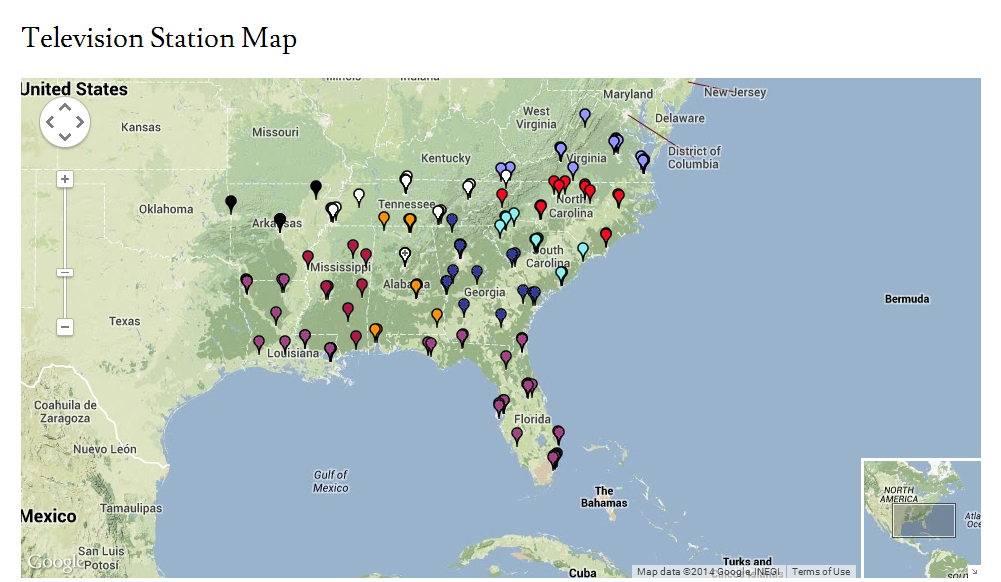

The second part of VST is a database that compiles data on each station and currently existing primary source materials. In its current state, VST provides a framework for documenting the location and content of primary source data related to the television station. Each of the map’s markers provide a link to a station Information page which details the television station’s address, the date the television station signed on if known, and the station’s call letters. Research is still ongoing, and VST will be updated as more data is found. However, at this stage every southern television station between 1942 and 1965 is represented on the map. As archival data is found, each television station’s page will be updated to include any information about where the television station’s archival data is housed, and how accessible it is. Overall, the project documents substantive local television footage content which was used to confront the very same issues that northern reporters and national broadcasts discussed. This local reporting is important because it gives us an eye into just how local stations covered live events which will give us a much clearer image of what television viewers actually saw. (See Figure 2)

Understanding local television stations is fundamental to understanding television’s influence on historical events, as the national networks had to use local stations to get to their viewership.

Citations

[1] Julian Bond, “The Media and the Movement: Looking Back from the Southern Front,” in Media, Culture, and the Modern African American Freedom Struggle, ed. Brian E. Ward (Gainesville: The University Press of Florida, 2001), 17, 27, & 29.

[2] Allison Graham, Framing the South: Film, Television and the South, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press (2001) p 1.

[3] Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement, (Chicago: University of Illinois, 2012) 2

[4] William L. O’Neill, American High: The Years of Confidence, 1945-1960 (New York: The Free Press, 1986), 255.

[5] Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 188.

[6] Ibid, 364.

[7] G. Calvin Mackenzie and Robert Weisbrot, The Liberal Hour: Washington and the Politics of Change in the 1960s (New York: The Penguin Press, 2008), 150.

[8] See WLBT’s coverage as discussed by Steven D. Classen Watching Jim Crow: the struggles over Mississippi TV, 1955-1969. Console-ing Passions. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2004, and Kay Mills, Changing Channels: The Civil Rights Case that Transformed Television. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004).

[9] Joan Zitzelman Programming in the Public Interest: A Perspective of WSB Television, 1948-1963 (University of Georgia, 1963), Appendix A 90-101.